The model making process drives our site analysis on our many projects. In our studio, we combine drone photography, geospatial mapping, field collected data, and topographic surveys to quickly create scaled plans of existing conditions. This process is greatly influenced by the work of the late Scottish designer Ian McHarg, who wrote the highly influential book “Design With Nature”. McHarg and his team of assistants famously would work on large mylar sheets to create scaled maps of soils, habitats, topographic relief, and other environmental features. These semi-transparent sheets would then be layered to create a combined map of a landscape.

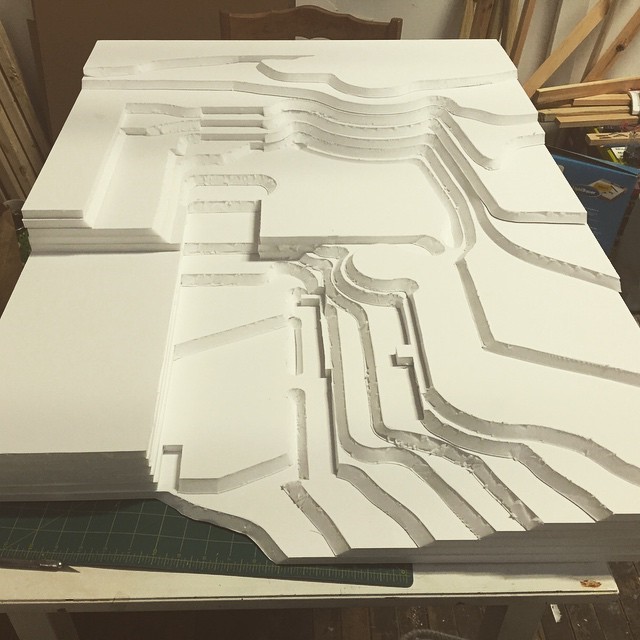

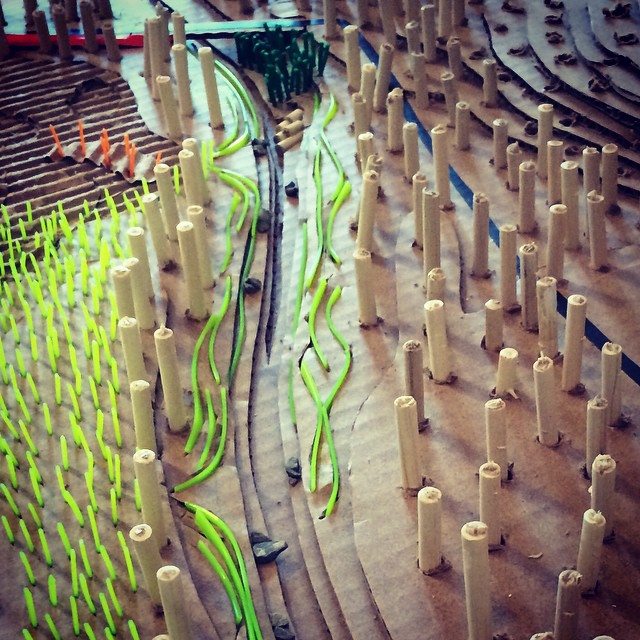

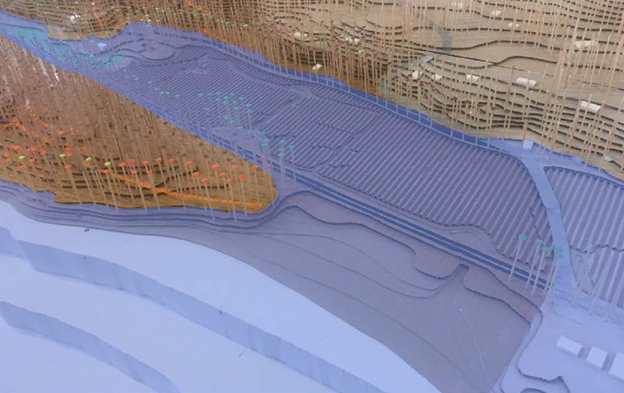

In the process of building a 3-D model, we almost always focus on topography to create a base, which normally also captures drainage patterns and viewsheds as well. We then overlay selected environmental layers, either by gluing or adding materials, to the topographic base. The result is a solid existing conditions three-dimensional map which we can later build into with our proposed design.

But why are models so valuable to us and our process, even when fewer and fewer people are using them?

Diving deeper as the designer

The conceptualization of the model itself is a great way for the designer to deeply explore the site at hand. The modeler can employ landscape ecology principles to consider different ecological systems within the landscape, how they function, and how they relate to each other. S/he must consider each entity within the landscape that is currently in existence, and how the removal or addition of new entities will affect the surrounding ecological systems and their interaction with humans. An environmental designer may also use a model to examine certain questions, such as how will the addition of tree plantings impact adjacent habitat? Or, if a pedestrian bridge is raised by three feet, how much of a viewshed will be opened up?

Communication with clients and collaborators

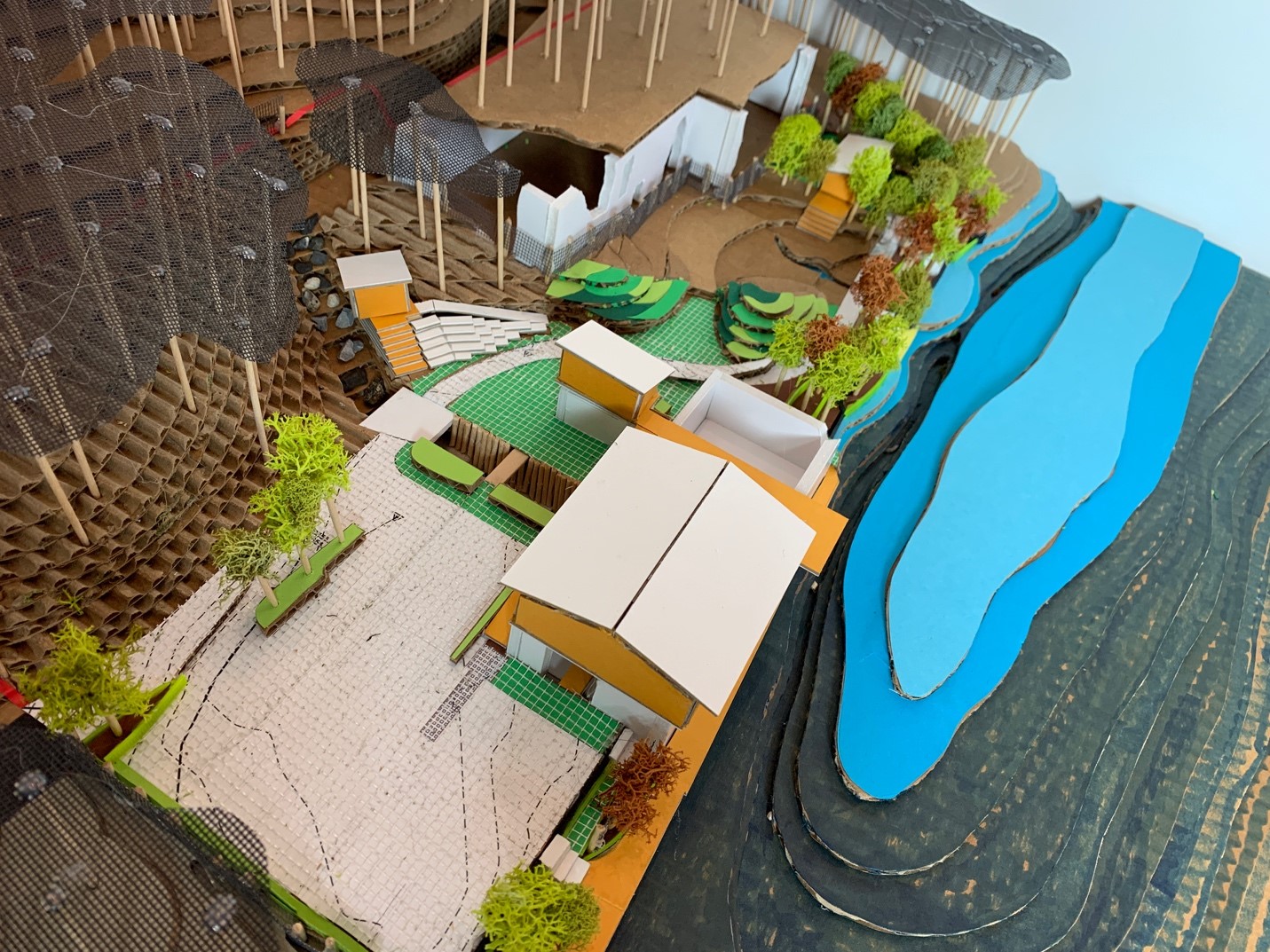

It can be difficult to convey the intent behind ecologically-inspired designs. Large ideas like landscape corridors, landforms, and hydrology are sometimes confusing to the layperson. Even in two-dimensional graphic plans, such real-world conditions often appear abstracted and confusing. In addition to creating an established understanding and shared vocabulary between designers and clients, models also improve lines of communication between professionals during collaborative work. Many of our projects entail significant modifications to large spaces, and we sometimes require the services of a diverse set of other consultants such as architects, civil engineers, planners, land use attorneys, and other professionals to advance our projects. A well-made site model allows them to immediately understand our initial concepts. Models also save time by enabling us to bypass complex engineering jargon and drawings in favor of simply pointing to locations of concern directly within the model. Since physical models are increasingly uncommon, use of models also sets a novel and engaging tone, indicating to our collaborators that our work together will be something special. When we enter a meeting and set down one of our 3’ by 4’ cardboard creations on the conference table, the mood brightens, and the professionals we work with tend to become more engaged.

Multiple scales and perspectives

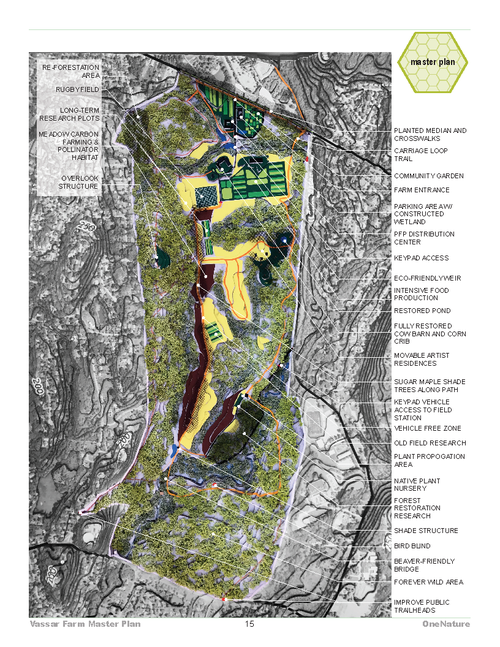

A well-made model can lead to specific critical views to advance and describe the design visions. These critical views can be overarching plans, like in the overhead view of a model we made for Vassar College’s Farm and Ecological Reserve. This view allows viewers to quickly understand the topography of the landscape, as well as proposed features will fit into the existing conditions. Another type of critical view is a perspective, like the image below, which shows a ground level perspective of a proposed council ring as part of a public park restoration. Perspectives allow clients to focus on specific features of the design plan and get a feel for them early in the process. Ultimately, the multiplicity of scales and perspectives provided by our models give clients a deeper understanding of their future landscape.

Simplification

It’s easy to get bogged down in details while working on large landscapes. By carefully selecting the scale and materials we use, we can keep the model vague in areas that might otherwise be distracting. For example, a woodland trail can be represented with dots of red masking tape. This does not mean the trail is intended to be red stepping stones, instead it means that the specifics of the path are not figured out yet, or that the materials of the path are much less important than its route and relationship to surrounding plant communities. Models are therefore able to help clarify complex situations by eliminating extraneous or less important elements of the design.

The images above show the progress from a simplified topographic model to a fully implemented landscape design at Safe Harbors Green.

Models were once much more widespread in the architecture and engineering industry. More recently, 3D computer modelling software has become the preferred method of representation. But the value of a physical model is a craft our studio has found exceptionally rewarding. Working on a computer screen without scale simply cannot compare with the fixed dimensions required by hand-made work and the self-determined orbital experience of an independent viewer. For every brilliant computer-created model or rendering, there are hundreds of sub-par creations. This is not to take away from the importance of computers in design, only to say that viable alternatives exist.

Many people experience monotony and health issues from computer-based work. Screens can really kill creativity. Our studio has found improved worker productivity and job satisfaction through reduction in screen time. Often, we have two or even three people working on a single model alongside ongoing discussions about a wide range of important topics.

Last but not least, even if the project is never fully realized, which is too often the case, working through ideas in model form creates real results in the form of art. Our models embody hundreds, sometimes thousands, of hours of devotion, discussion, and research. Once in a final form we can enjoy them in our studio in years to come.